Why are central banks reporting losses? Does it matter to you ?

The losses of Central Banks pose a risk to their financial independence and credibility ? Will the Federal Reserve go bankrupt ? #deferredassets #Fed #ECD #Losses # Economy

Central banks in advanced economies have been actively using their financial resources to ensure economic stability, particularly noticeable after the Great Financial Crisis, the European debt crisis, and the COVID pandemic. They've implemented various programs like asset purchases and lending to achieve their goals. Many central banks are facing losses due to rising interest rates, which they implemented to control high inflation. These losses could continue and potentially grow in the upcoming years. Do these ongoing losses pose a risk to the financial autonomy and trustworthiness of central banks?

Will the Federal Reserve go bankrupt ?

Time to learn!

Key Takeaways:

Central banks are not commercial banks Their purpose is to act in the public interest. The policy mandates of central banks include price stability and financial stability, but not profit maximisation.

Federal Reserve(Fed), Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), National Bank of Belgium (NBB), Bank of England (BoE), Bank of Japan, Netherlands Bank (DNB), Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), and Sveriges Riksbank have announced losses.

Central banks usually transfer their profits to the Ministry of Treasury and Finance. In case of a loss, we can say that no money can be transferred to the Ministry of Treasury and Finance for the relevant year.

Central Banks are not subject to capital adequacy requirements or bankruptcy procedures and can operate effectively even with negative equity, as the central banks of Chile, the Czech Republic, Israel and Mexico have done over several years.

Dutch National Bank indicated that temporary negative capital is permissible and workable.

The CNB (Czech National Bank) actually had negative equity for 16 years, from 1998 until 2013.

Over the last 20 years, about a third of the central banks in small open economies have experienced negative equity, without it impacting their ability to fulfill their mandates.

Introduction

In the second week of 2024, the Federal Reserve (Fed) issued a statement1 that was not reported in the business press. The statement disclosed that, by the end of 2023, the Fed's expenditures had exceeded its revenues, resulting in a loss for the year. This loss was to be accounted for under an item termed 'deferred assets”. Not only the US Federal Reserve but also several other central banks have announced the losses. These include the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), National Bank of Belgium (NBB), Bank of England (BoE), Bank of Japan, Netherlands Bank (DNB), Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), and Sveriges Riksbank2. Up until the 2008 financial crisis, the consensus among economists seemed to be that central banks experiencing periods of negative capital were a phenomenon confined to ‘mostly Latin American countries with a history of monetary instability.3

Central banks have been using their financial resources more actively in recent years to help stabilize their economies and achieve economic goals. Following the major financial crisis in the late 2000s, many central banks in developed countries started buying assets or launching lending programs to support their policies. Similarly, during the Covid-19 pandemic, several central banks introduced new programs.

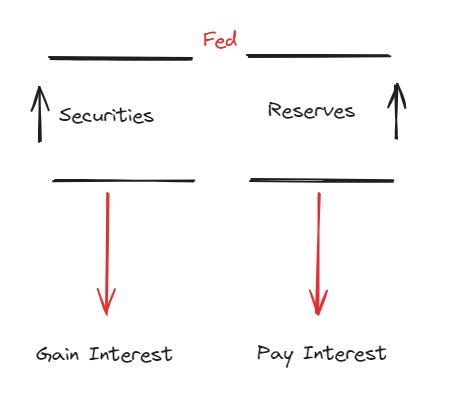

The diagram shows that when the Fed buys assets, it increases its holdings of securities from which it earns interest, and it also increases the reserves held by commercial banks, on which it pays interest*. Central banks in advanced countries have expanded their balance sheets through these operations, with their balance sheets now amounting to 60% of their GDPs4. The remuneration on reserves is closely linked to policy interest rates, and has thus risen rapidly.

By raising interest rates to combat inflation, the interest paid on reserves has increased. In contrast, on the asset side, the securities were mostly long-term fixed-rate bonds** that generate a relatively stable stream of income. Consequently, this has led to a decrease in the net interest income of central banks.2

What would be the impact of these losses on the economy ?

Central banks usually transfer their profits to the Ministry of Treasury and Finance. In case of a loss, we can say that no money can be transferred to the Ministry of Treasury and Finance for the relevant year. The annual impact on the general government fiscal balance should in general be modest: over 2015-21, revenues from the central banks considered in Figure rarely exceeded, and were often far below, 0.5% of GDP per year.5

The policy mandates of central banks include price stability and financial stability, but not profit maximisation. Moreover, central banks are not subject to capital adequacy requirements or bankruptcy procedures and can operate effectively even with negative equity, as the central banks of Chile, the Czech Republic, Israel and Mexico have done over several years. 2 Furthermore, over the last 20 years, about a third of the central banks in small open economies have experienced negative equity, without it impacting their ability to fulfill their mandates.9

Dutch National Bank wrote letter to his Ministry of Finance. He indicated that temporary negative capital is permissible and workable.6

The LOSSES in a given year may simply offset a portion of the EXPECTED PROFITS in the next years. When Fed’s income is not sufficient to cover interest expense, realized losses, operating and other expenses, a deferred asset is created. 7 You can see this item from last H.4.1 Factors Affecting Reserve Balances (in liabilities).8

Positive amounts represent the estimated weekly remittances due to U.S. Treasury***. Negative amounts represent the cumulative deferred asset position, which is incurred during a period when earnings are not sufficient to provide for the cost of operations, payment of dividends, and maintaining surplus. The deferred asset is the amount of net earnings that the Federal Reserve Banks need to realize before remittances to the U.S. Treasury resume.

The ECB announced that it will cover the losses from its profits of the previous year9. They expect that, over time, losses will decline because the income earned by the Eurosystem central banks on their bonds and other assets, and from the loans they give to commercial banks, will also rise.10 ****

The conventional balance sheet of the Fed or of any other central bank is a completely unreliable guide to and indicator of the financial health.11 People generally confuse commercial banks with central banks, leading to the mistaken belief that central banks can become insolvent like commercial banks. Commercial banks may become insolvent under two conditions: the failure to pay the obligations, known as equitable insolvency, and the condition when liabilities exceed assets, known as balance sheet insolvency. Central banks are considered the equitably solvent because they can always meet their obligations by creating money(reserves). They are also regarded as balance sheet solvent because they can offset the losses using several methods, such as using expected profits in the next years, buying newly issued treasury bonds, employing financial buffers and using profits of the previous year.

Central banks also have considerable control over the values of the main policy parameters that affect their profits such as short-term interest rates, currency pegs, and involvement in operations that may expose them to considerable losses (e.g., bailouts or purchases of risky assets). In addition, central banks determine the amount of required reserves that commercial banks must deposit at the central bank and the interest on such deposits. Due to their unique regulatory position and monopoly power on the supply of base money, central banks enjoy more inelastic demand for their “products” than most firms do.12

Despite this reality, central banks occasionally fall into the trap of unrealistic judgments influenced by the press and politicians. They strive to present profits in their balance sheets.

The case of the ECB’s governance of its balance sheet reveals that although Europe’s monetary policy-makers are well aware of the irrelevance of central bank capital in theory, they nevertheless insist on maintaining positive capital in practice. When probing into the reasons behind this incongruence, the available evidence suggests that policy-makers deem themselves constrained by the general public’s misperceptions of central banking. In particular, non-experts are believed to disapprove of the central bank in case policy outcomes deviated from the ‘common sense’ that losses and negative capital are ‘not good’, in line with household reasoning.13

The CNB (Czech National Bank) actually had negative equity for 16 years, from 1998 until 2013. Its negative equity peaked at almost CZK (Czech Koruna) –200 billion in 2007, which, at that time, was equivalent to slightly less than 5 percent of the annual GDP.14

Conclusion

Central banks fundamentally differ from commercial banks in their objectives and operational frameworks. Their primary mandate is to serve the public interest, focusing on maintaining price and financial stability rather than pursuing profit maximization. Several central banks have reported losses. Significantly, central banks operate without the constraints of capital adequacy requirements or bankruptcy procedures, allowing them to function effectively even with negative equity. This has been demonstrated by central banks in Chile, the Czech Republic, Israel, and Mexico, which have operated with negative equity for extended periods. A notable example is the Czech National Bank (CNB), which operated with negative equity for 16 years, from 1998 to 2013. The Dutch National Bank has acknowledged that temporary negative capital is both permissible and feasible.

Engin YILMAZ (

)Notes:

*We should note here that interest is paid only on reserves lent to central banks.

**Higher interest rates also reduce the market value of securities. Valuation losses may thus arise, though this depends on the accounting frameworks and asset sales decisions of central banks. For instance, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan account for securities held for monetary policy purposes using amortised cost. This means that valuation changes do not affect profits unless securities are sold, which has not been the case so far. Eurosystem accounting guidelines, also followed by Sweden, allow central banks to value securities held for monetary policy purposes at either amortised cost or the current market price. Mark-to-market accounting brings forward loss recognition, as also illustrated by Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. In Switzerland, the central bank loss was unusually large in 2022, at 17 per cent of GDP, but these losses stemmed largely from changes in the domestic currency value of foreign exchange reserves, including foreign securities. 4

***Central Bank has either both public and private ownership or only private ownership, the amount of profit that can be distributed to private shareholders is typically subject to a cap (ranging from 6% to 12% of the nominal value of the paid-up capital), while the remaining distributable profit, net of any transfers to equity (capital and reserves) goes to the government. More detailed information on the methods that central banks use in the profit allocation/distribution regime is indicated in Annex 1 of this article.15

****PROTOCOL ON THE STATUTE OF THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM OF CENTRAL BANKS AND OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK (Article 29 and 33), Link

******Congress View16

Sources

Federal Reserve Board announces preliminary financial information for the Federal Reserve Banks’ income and expenses in 2023, (2024), Link

Sarah Bell, Michael Chui, Tamara Gomes, Paul Moser-Boehm and Albert Pierres Tejada, (2023), Why are central banks reporting losses? Does it matter? , Link

Sebastian Diessner, (2023), The political economy of monetary-fiscal coordination: central bank losses and the specter of central bankruptcy in Europe and Japan, Review of International Political Economy, Link, Link Thesis

Carpenter, S., Ihrig, J., Klee, E., Quinn, D. and Boote, A. (2013), “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and Earnings: A Primer and Projections”, FED Finance and Economics Discussion Series, No 1, September,Link

Profits and losses of the ECB and the euro area national central banks: where do they come from?, (2023), Link

Willem Buiter (2008), Can Central Banks Go Broke? European Institute, LSE, Universiteit van Amsterdam and CEPR, Link

IGOR GONCHAROV, VASSO IOANNIDOU, MARTIN C. SCHMALZ, (2021), (Why) Do Central Banks Care about Their Profits?, Link

Sebastian Diessner, (2023), The power of folk ideas in economic policy and the central bank–commercial bank analogy, New Political Economy, 28:2, 315-328, Link