Quantifying the Fed Funds Rate Response to Reserve Supply Changes or When Are Central Bank Reserves Ample?

Quantifying the Fed Funds Rate Response to Reserve Supply Changes or When Are Central Bank Reserves Ample?

The Fed recently published new research on the ample reserve regime and developed an econometric model to determine whether reserves are scarce or ample. A team of seven researchers, led by chief researcher Gara Afonso, contributed to this work. I aim to summarize the following articles and posts in my blog.

Fed’s Team:

Gara Afonso, Kevin Clark, Brian Gowen, Gabriele La Spada, JC Martinez, Jason Miu, and Will Riordan

Articles and Posts:

When Are Central Bank Reserves Ample?1 , A New Set of Indicators of Reserve Ampleness2 , Scarce, Abundant, or Ample?3 and How Abundant Are Reserves? Evidence from the Wholesale Payment System4

Summary

The Federal Reserve has initiated a two-pronged approach to assessing reserve ampleness. First, a model was developed to estimate the elasticity of the federal funds rate to reserve changes, providing a quantitative measure of reserve sufficiency. Second, a set of complementary indicators, derived from money market data and bank liquidity metrics, offer additional insights into reserve conditions. By combining these tools, policymakers can more accurately monitor reserve levels and identify potential scarcity risks.

What is the ample reserve regime? (I)

The Federal Reserve (Fed) implements monetary policy in a regime of ample reserves, whereby short-term interest rates are controlled mainly through the setting of administered rates.

What is the ample reserve regime? (II)

The reserves are ample when the supply of reserves is sufficiently large that the fed funds rate is not materially sensitive to everyday changes in aggregate reserves. In other words, in an ample reserve regime, the fed funds rate can respond to daily shocks, but the response must be small; or, to put it differently, the elasticity of the fed funds rate to reserve shocks must be small, so that active management of the supply of reserves by the Fed is not necessary.

Question:

To do so, the quantity of reserves in the banking system needs to be large enough that everyday changes in reserves do not cause large variations in the policy rate, the so-called federal funds rate. As the Fed shrinks its balance sheet , how can it assess when to stop so that the supply of reserves remains ample.

Answer:

The answer is that this elasticity depends on the quantity of reserves in the banking system through the so-called reserve demand curve, which describes the relationship between the fed funds rate and aggregate reserves that stems from banks’ demand for reserves. The elasticity of the fed funds rate to reserve shocks, in fact, is simply the slope of this curve: it tells us by how much the fed funds rate changes in response to a small shift in reserve supply. The point here is that the slope of the reserve demand curve becomes steeper as reserves decline.

Scarce Reserves Regime: In this region, the demand curve is steeply sloped, indicating a strong negative relationship between the federal funds rate and the supply of reserves. As the supply of reserves declines, the federal funds rate increases significantly.

Ample Reserves Regime: Here, the demand curve is gently sloped, showing a weaker negative relationship between the federal funds rate and the supply of reserves. As the supply of reserves declines, the federal funds rate increases, but at a slower pace compared to the scarce reserves region. The elasticity of the federal funds rate is negative but small in this region.

Abundant Reserves Regime: In this region, changes in the supply of reserves do not affect the federal funds rate. The elasticity of the federal funds rate is zero.

To maintain ample reserves, the Fed should target a reserve level where the demand curve begins to flatten.

The shifting demand for reserves by banks, coupled with the Fed's reactive supply management, makes identifying the transition point between abundant and ample reserves a complex task.

Solution:

“Real-Time” daily estimates of the slope of the reserve demand curve: Fed estimates the slope of a linear function with time-varying coefficients and stochastic volatility at the daily frequency.

The slope represents the elasticity of the fed funds rate to shocks in the supply of reserves: it shows by how many basis points the fed funds rate would change for an increase in aggregate reserves equal to 1 percent of banks’ total assets.

The 4 Indicators of Reserve Ampleness

Late Payments: Throughout each business day, banks use their accounts at the Fed to make and receive payments, transferring reserves over a system known as Fedwire® Funds Service. As the supply of reserves declines and transitions from abundant to ample, banks have an incentive to postpone their outgoing payments, pushing the settlement towards the end of the business day to ensure they have sufficient reserves to settle their transactions.

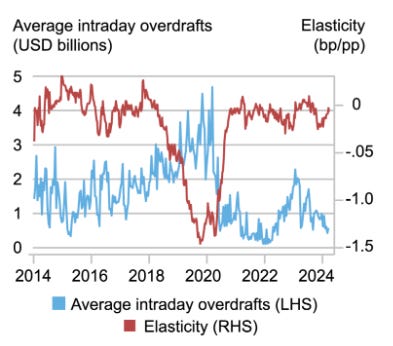

Banks’ Intraday Overdrafts: If banks’ ability to postpone outgoing payments is limited, they may increase their use of intraday credit provided by the Fed, known as daylight or intraday overdraft. A bank incurs an intraday overdraft when the balance in its account at the Fed is negative during the business day. As reserves become less abundant and banks more liquidity constrained, we would expect to observe more intraday overdrafts.

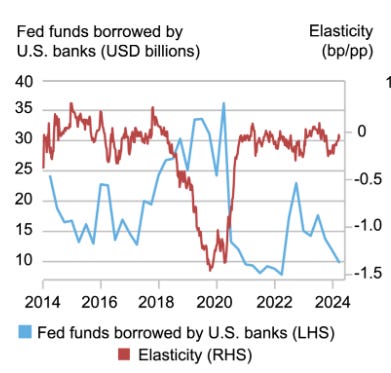

Domestic Borrowing in the Fed Funds Market: The domestic banks predominantly borrow in the fed funds market when they need short-term liquidity. An increase in the volume of fed funds borrowing by domestic banks could therefore signal that reserves are becoming less abundant as banks are more liquidity constrained.

Upward Pressure in Repo Rates: Rates on overnight repurchase agreements (repos) can influence the fed funds rate because repos and fed funds are close substitutes for many market participants.

The four indicators of reserve ampleness have been consistent with Fed’s real-time estimate of the fed-funds-rate elasticity to reserve shocks.

Engin YILMAZ (

)

References

Gara Afonso, Domenico Giannone, Gabriele La Spada, and John C. Williams , “When Are Central Bank Reserves Ample? ,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 13, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/08/when-are-central-bank-reserves-ample/.

Gara Afonso, Kevin Clark, Brian Gowen, Gabriele La Spada, JC Martinez, Jason Miu, and Will Riordan, “A New Set of Indicators of Reserve Ampleness,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 14, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/08/a-new-set-of-indicators-of-reserve-ampleness/.

Gara Afonso, Domenico Giannone, Gabriele La Spada, and John C. Williams , “Scarce, Abundant, or Ample? A Time-Varying Model of the Reserve Demand Curve ” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April, 2024, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr1019.html

Gara Afonso, Domenico Giannone, Gabriele La Spada, and John C. Williams , “How Abundant Are Reserves? Evidence from the Wholesale Payment System ” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April, 2022, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr1040