In this post, I’ll share a summary and key insights from Charles R. Morris’s The Two Trillion Dollar Meltdown: Easy Money, High Rollers, and the Great Credit Crash. From portfolio insurance in 1987, to the mortgage derivatives boom of the 1990s, and finally the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998, Morris traces how mathematical elegance repeatedly collided with market reality.

The Rise, Fall, and Recovery of Mortgage-Backeds

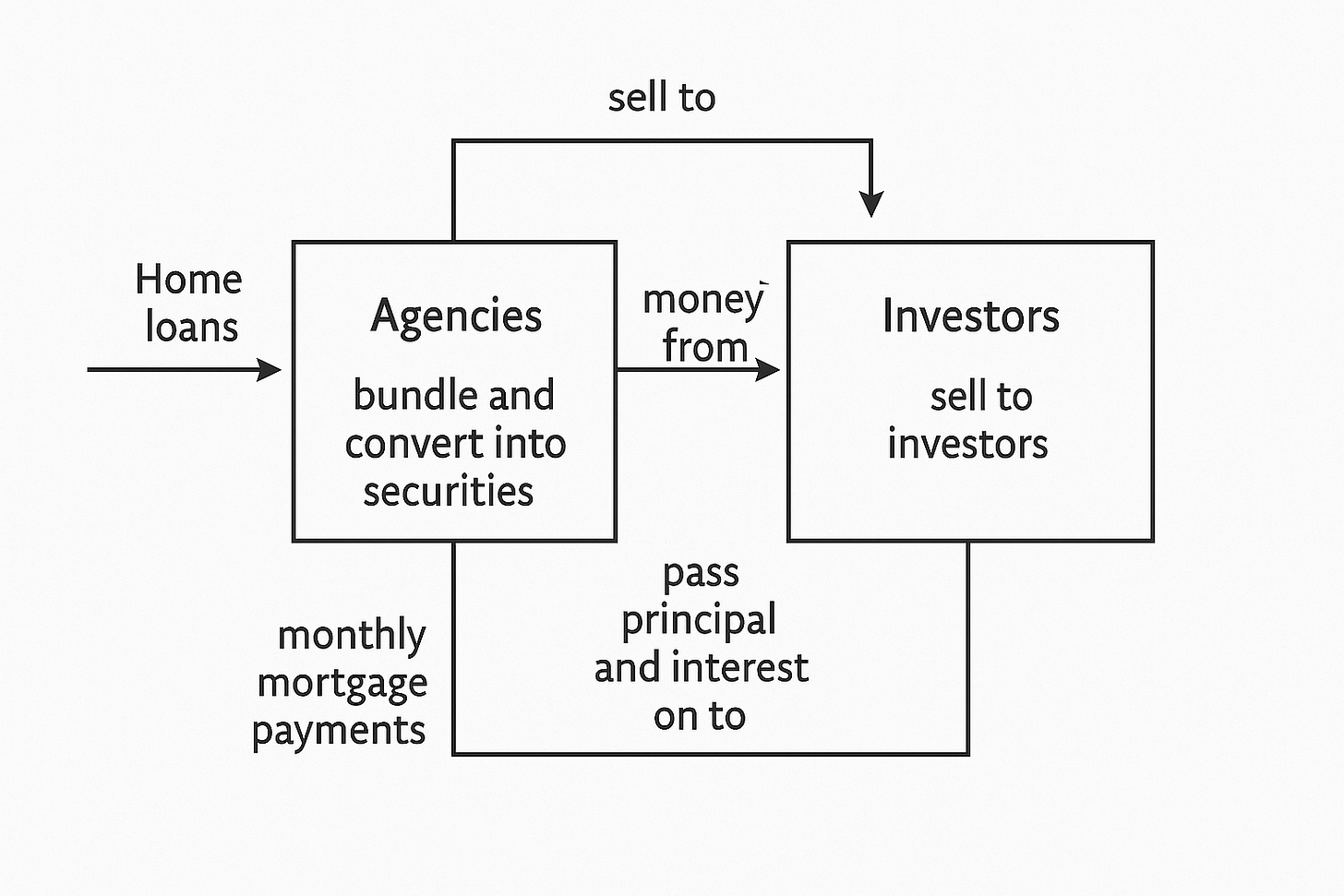

The New Deal adopted S&Ls, or savings-and-loan banks, as the linchpin of its strategy for broadening opportunities for home ownership. To keep S&Ls in lendable funds, the government also created quasi-federal agencies-Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae, and Freddie Mac-that could liquefy local lending markets by buying up mortgages from S&Ls and other qualified lenders. The agencies in turn learned to maintain their own liquidity by selling mortgage-backed securities, or mortgage pass-throughs. A pass-through is created by transferring a slug of mortgages to a trust, which in turn issues certificates representing a pro rata slice of all the principal and interest it receives. (P:38)

The agencies buy home loans from banks, then bundle and convert them into securities that they sell to investors. The money from these investors goes back to the banks, allowing them to issue new loans. Over time, the banks collect monthly mortgage payments from homeowners and send those payments to the agencies, which then pass the principal and interest on to the investors.

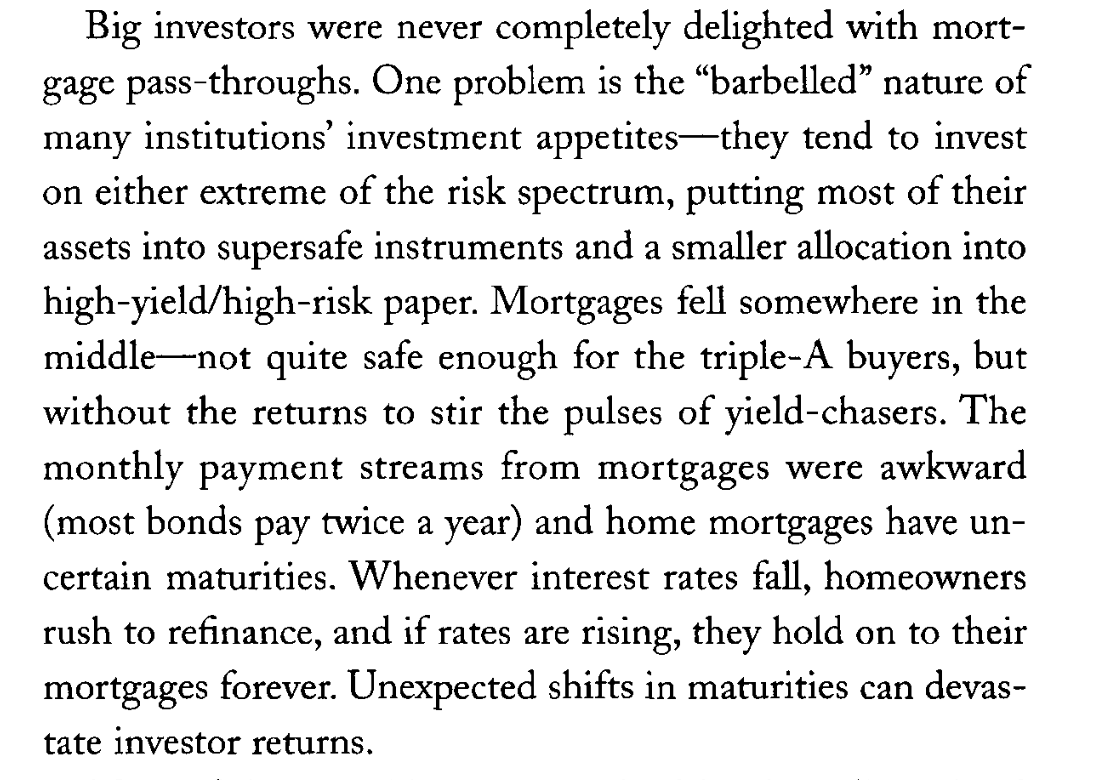

Problems

Problems were solved by the collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO)

Mortgages were divided into three tranches (layers) with different risk and return levels.

The top tranche (≈70%) got first claim on payments, making it very safe and rated AAA, but with low returns.

The middle tranche (≈20%) offered moderate risk and yield.

The bottom tranche (≈10%) took the first losses but earned high, junk-bond-level returns.

In essence, CMOs turned one pool of mortgages into bond-like products that catered to different investor risk appetites.

💥 Why the 1994 rate hike “ended the party”

CMOs (Collateralized Mortgage Obligations) depend heavily on interest rate stability because their value comes from predictable mortgage payments.

When the Federal Reserve raised the federal funds rate by 0.5% unexpectedly in early 1994:

Mortgage rates rose, so fewer people refinanced or took new loans.

→ That slowed down cash flows from the mortgage pools.Existing CMOs lost value because investors demanded higher yields to match the new, higher-rate environment.

→ Bond prices fall when interest rates rise.The complex models that priced CMOs assumed stable or falling rates.

→ The sudden hike broke those models, making investors unsure how to value the tranches.

The 1987 Stock Market Crash

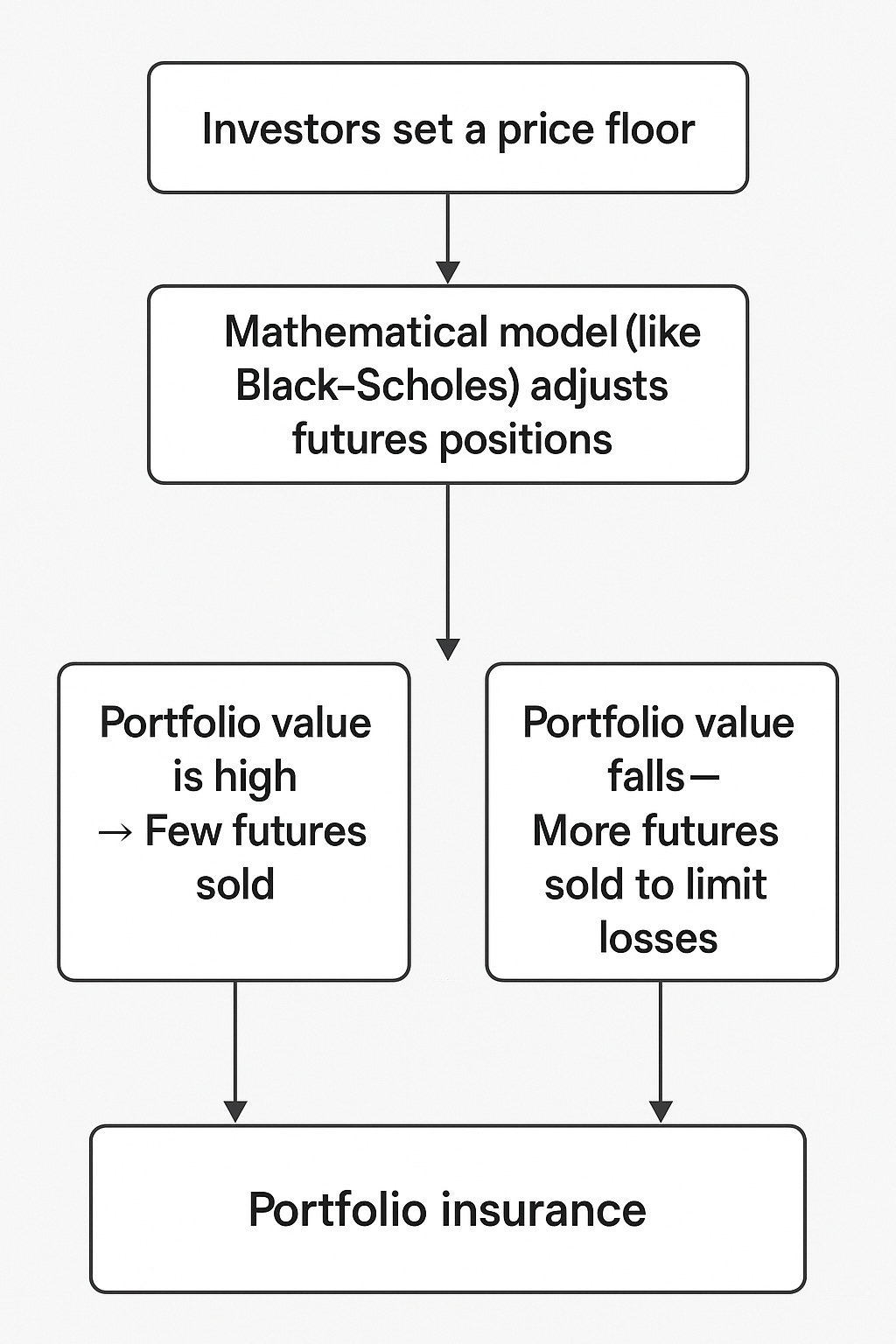

If stocks rise, you’ll lose money on the futures, but if stocks fall, your futures profits will offset your market loss. The specifics were devised by two University of California-Berkeley finance professors, Hayne Leland and Mark Rubinstein. The investor chooses a desired price floor for the portfolio, then Black-Scholes-type math is used to design the futures strategy. When a portfolio is well above its floor, future sales are minimal, but if a portfolio starts to fall, future sales steadily increase to keep gains and losses roughly balanced.(P:46)

Investors set a price floor, and a mathematical model (like Black-Scholes) adjusted futures positions:

When the portfolio value was high → few futures sold.

When it fell → more futures sold to limit losses.

This method was called portfolio insurance.

Problem

💥 Black Monday: On October 19, 1987

On October 19, 1987 — “Black Monday”, a massive wave of automated futures selling triggered by portfolio insurance programs caused markets to collapse.

At the opening, trading in Chicago and New York quickly broke down as sell orders overwhelmed buyers.

Prices plunged so fast that many major stocks didn’t open for hours.

Futures fell even harder, at times having no buyers or clear price.

The New York Stock Exchange invoked emergency “circuit breakers” and even considered closing.

By the end of the day, U.S. stocks had fallen 23%, the largest one-day percentage drop in history, spreading panic worldwide and exposing the fragility of automated trading systems.

The LTCM Crash

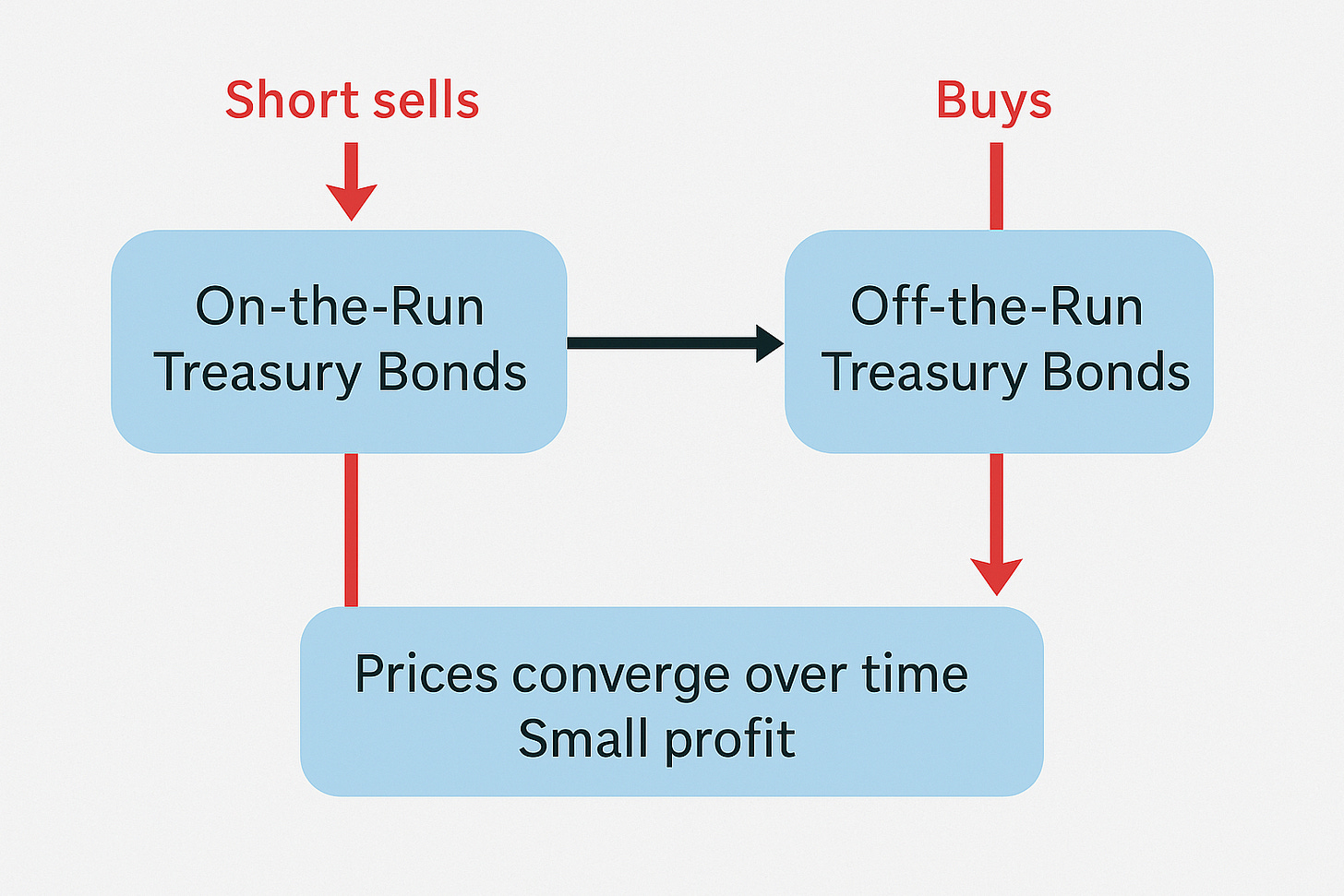

Meriwether and his team were relative value traders. They tracked price relationships between comparable instruments, looking for price divergences that their models said were unjustified. A standard example is the trading spread between on-the-run and off-the-run Treasury bonds. On-the-runs are the most recently issued bonds, and since they have more trading activity, they usually trade at slight premiums to older bonds. But the premium will disappear with time. So the trader shorts the on-the-run issue (sells bonds he doesn’t own) and buys off-the-runs with the proceeds. By the time he closes out the transaction, prices normally will have moved back together, and he will make a small profit. Such arbitrage strategies are usually quite safe. It makes no difference if bond prices rise or fall, so long as the relative prices of the two move closer together. Occasionally, they don’t, but Black-Scholes tells you those are rare occurrences.(P:50)

They focused on arbitrage trades like the spread between newly issued (on-the-run) and older (off-the-run) Treasury bonds — selling the newer ones and buying the older ones, expecting their prices to converge over time. This strategy aimed for low-risk, steady profits, since overall market movements didn’t matter — only the relative price difference. According to financial models like Black-Scholes, big deviations from this pattern were expected to be rare.

Problem

💥 LTCM was dead: 100-to-1 leverage

When Meriwether opened his books to Fed staff in late September, they were shocked. No one had imagined that LTCM had positions in excess of$100 billion, on an equity base that had shrunk to only $1 billion. LTCM was clearly insolvent and, at the rate its positions were exploding, would soon have no equity at all.